Paraquat pesticide maker used “weak” data on Parkinson’s

By Malcolm PriorBBC News rural affairs producer

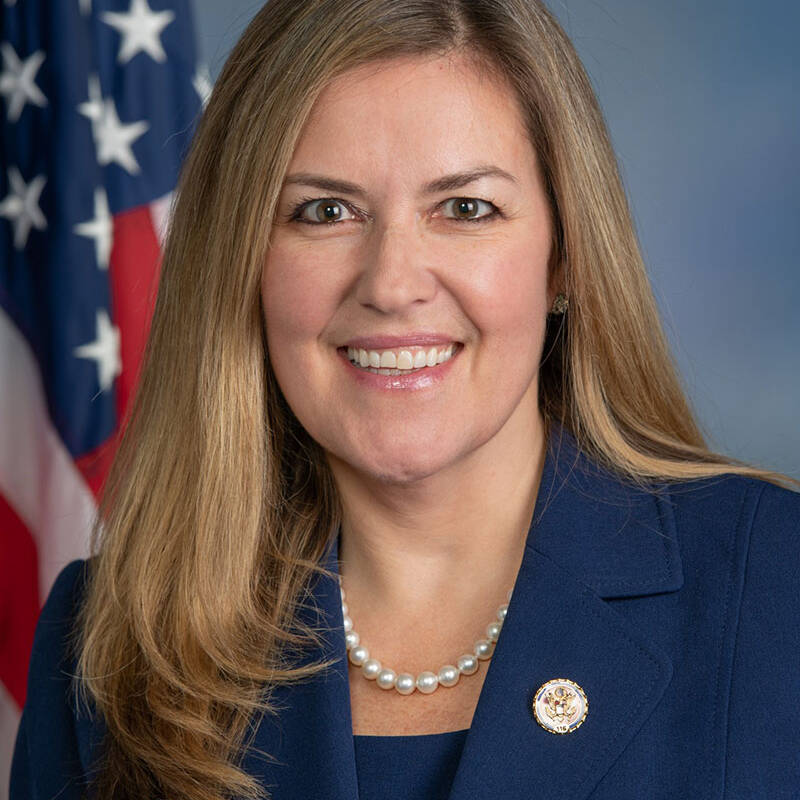

Larry Wyles

Larry WylesA chemical manufacturer facing legal action over alleged links between its pesticide and Parkinson’s Disease ignored key health records in studies.

Syngenta insists there is no evidence of a Parkinson’s link to the toxic Paraquat, which is made in the UK.

But the BBC has seen legal documents in which it admits it only looked at death certificates, rather than the medical records, of workers at its Widnes site.

Syngenta is fighting legal action by thousands of farmers in the US.

In court documents, the company’s chief medical officer acknowledged it did not look at whether any living former workers had Parkinson’s Disease. Instead it only looked at causes of death, even though experts say the condition was underreported on death certificates at the time.

Charity Parkinson’s UK is now calling for “more robust and independent research” into any link between pesticides, including Paraquat, and Parkinson’s.

Larry Wyles

Larry WylesThe pesticide has not been authorised for use in the UK since 2007 but it is still made at Syngenta’s plant in Huddersfield and exported to countries such as Japan, Australia and the US.

Eighty-year-old former farmer Larry Wyles, from Lebanon, Pennsylvania, is one of the plaintiffs with Parkinson’s Disease in the US legal action.

Mr Wyles used the pesticide on his own farm for more than two decades but also as a child on his father’s farm.

“Back in those days we did not have very good machinery and I remember having to clean out the nozzles on the sprayer,” he told the BBC.

“I would blow the nozzles and the Paraquat would get on my hand and all over my clothes. I didn’t know at the time what it was doing to me, neither did my father.”

Larry Wyles

Larry WylesMr Wyles was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease in 2002, which he says affects “every facet of my life. It’s a horrible disease.”

“It’s so consuming and it’s done my life in as far as my relationship with my wife. It’s tough because I am needy and I was never needy. I was always very independent and today I need help with most everything,” he explained.

He told the BBC that Syngenta “ought to be banned from making Paraquat ever again. They should be told to take it off the shelves today. I was never told how detrimental it would be to my health.”

That was a call backed by Julie Plumley, who runs a care farm in Dorset and whose late father was a farmer who used Paraquat and later had Parkinson’s Disease.

She said of how the Syngenta study was carried out: “In my eyes they are trying to protect the company.”

Syngenta’s study of workers involved in the manufacture of Paraquat at its former Widnes site rejected any link with the disease in 2011 and again in 2021 by looking at causes of death recorded on death certificates.

The company has always said it had carried out “long-term monitoring” of workers at the site which showed “no increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease in the workforce who manufactured Paraquat.”

The research has become a key part of the company’s defence in the ongoing legal action taken by US farm workers against the manufacturer.

But, in the US litigation, the company’s chief medical officer, Dr Clive Campbell, who co-authored the research, has acknowledged it never looked at the health records of those workers still alive, which it had access to.

Getty Images

Experts say Parkinson’s Disease is underreported on death certificates and would not show the true numbers affected.

The legal papers from the US litigation also show the research was rejected by three different academic journals because it did not look at the health of living workers.

The documents further illustrate that the company already knew in 2009 that Parkinson’s was not mentioned in high numbers on death certificates data they already held before it decided to conduct the wider mortality study.

Syngenta told the BBC that it had “considered conducting a morbidity study of the Paraquat manufacturing workforce and consulted with expert external epidemiologists to solicit their views.

“They advised Syngenta that the cohort of Paraquat manufacturing workers was too small, especially when considering the anticipated participation rate, for a morbidity study to yield informative results.”

It added that it did not have access to the “comprehensive medical records of the cohort – only the occupational health records of those who attended skin clinics”.

While the company acknowledged that in the 2011 and 2021 publications of the Widnes study not all cases of Parkinson’s were always listed on death certificates, it said “the same would be true of the general population data which were used as a comparator in the study”.

They added that the publications were “only two among more than 1,200 safety studies conducted in the 60 years since Paraquat was first registered, both by Syngenta and independent researchers.”

In a statement provided to the BBC, it said: “Despite decades of investigation and myriad epidemiological and laboratory studies, no scientist or doctor has ever concluded in a peer-reviewed scientific analysis that Paraquat causes Parkinson’s.”

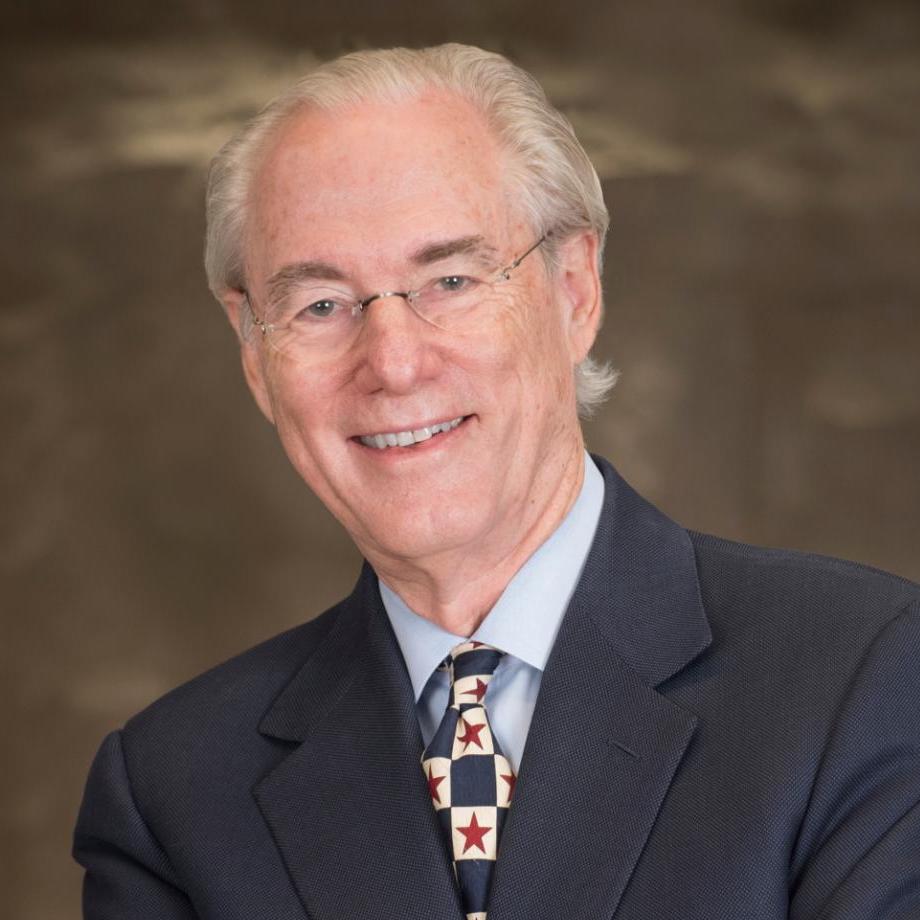

Radboudumc

The US regulator, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which is facing a legal challenge to its approval of Paraquat, said that its current review of the herbicide’s use was looking at what measures might be needed to mitigate any health risks.

Last month, its draft report said the benefits of using Paraquat outweighed the health risks but that it had still to look at 90 submissions, including scientific studies, concerning the risks of Parkinson’s.

Of the Syngenta study, the EPA told the BBC: “For an outcome like Parkinson’s Disease, mortality is unlikely to be a reliable indicator for evaluating an association.”

Leading expert Professor Bas Bloem, director of the Radboudumc Center of Expertise for Parkinson & Movement Disorders in the Netherlands, insisted that “scientists across the globe are convinced Paraquat is a cause of Parkinson’s.”

He pointed to the most recent epidemiological study – carried out by UCLA’s Department of Neurology and published this month – to find that Paraquat exposure increases the risk of Parkinson’s Disease. He said: “The arguments against Paraquat are piling up.”

Of Syngenta’s own workers mortality study, he said: “The fact that it is authored by Syngenta lowers the value of this publication. There are methodological issues. It is not heavyweight evidence at all.

“Without a careful clinical analysis, just using mortality as a crude outcome has very limited value.”

Independent medical experts in the UK have also told the BBC that Parkinson’s Disease would have been underreported in death certificates and a full survey of living workers’ health and medical records would have been more useful.

One of those experts is Professor Peter Hobson, a clinical healthcare scientist who carried out a 2018 study of whether death certificates accurately recorded Parkinson’s Disease.

He said that “employing death certificates alone to determine increased risk of developing any neurological condition is very weak and will always have questionable reliability.”

Because of the weak methodology used, he said he did not believe “anyone with even a basic understanding of epidemiology would support the company’s claim that there is no increased risk of developing Parkinson’s.”

Professor David Dexter, director of research at Parkinson’s UK, said that, while evidence was not yet strong enough to prove pesticides, including Paraquat, directly cause Parkinson’s, international studies “overall suggest that exposure to pesticides may increase risk of the condition”.

“We need more robust and independent research… including studies looking at occupational exposure, to help us understand the role these chemicals may play in the development of the condition,” he added.

Larry Gifford, president of campaign group PD Avengers, based in Canada, said: “Syngenta seems more interested in safeguarding long-term commercial interests than upholding scientific rigor.

“A decade passing between publications without actively monitoring Parkinson’s cases among the living workforce? It goes beyond being noteworthy; it’s outright outrageous.”

Syngenta told the BBC that it “is and has always been devoted to pursuing and implementing the best available science to ensure the safety of users and farmers.

“Syngenta has spent millions of dollars over decades to stay abreast of the independent scientific literature related to the safety of Paraquat and has conducted hundreds of studies evaluating the safety of Paraquat.”

They added that “it is important to note that Paraquat is safe when used as directed.”